Stay

Dream Weavers – Thatch Of The Day

Images of tropical buildings almost always include a thatched roof. Whether on a fare, bale or

hale, or something more elaborate like the soaring roof of a grand lobby entrance to a luxury

hotel. What began life centuries ago as a cheap way of staying dry has evolved into an island

icon, says Toby Preston.

Pacific Island Living

November 24, 2020Here in the Pacific we tend to think of the thatched bure or fare and a swaying palm as the archetypical tropical building meme, and to a large extent it is. It’s just that thatching is a roofing tradition that goes back centuries and has been employed in buildings across the world. Indeed there are more than 60,000 thatched buildings in the United Kingdom and many more across Europe.

The use of thatch was an obvious solution for ancient builders because of the availability of reeds, straw, rushes or palm fronds. The same applies today throughout our region, and given its instant familiarity as a tropical material it’s widely used in many modern resorts and hotels as well as for the most minimal and basic structures. One advantage I noticed after some damage to one of my natangura (the Vanuatu palm used for thatching) roofs after cyclone Pam was the ease with which it can be patched or replaced. A team of local boys was on the roof within hours of the passing of Pam, laying new palm fronds over the damaged sections and propping up a leaning woven bamboo and natangura structure with poles and ropes, after which it was as good as new. I did however lose two beachfront fares completely; all that was left were a couple of concrete footings used to secure the posts, the remainder disappeared never to be seen again. I have since given up on building anything on the beach, having now rebuilt twice after storm surges and cyclones – I was warned by one of my Ni-Vanuatu friends that the sea simply reclaims beaches on a regular basis and it’s useless trying to resist. She was right.

Speaking of repair work using new thatch over old, it’s said that in some cases old buildings have layers of thatch laid over centuries which are now up to two metres thick. Here in the tropics we tend to just rip it off and start again so the structure remains very light and can be easily supported by bush timber in lots of simpler buildings.

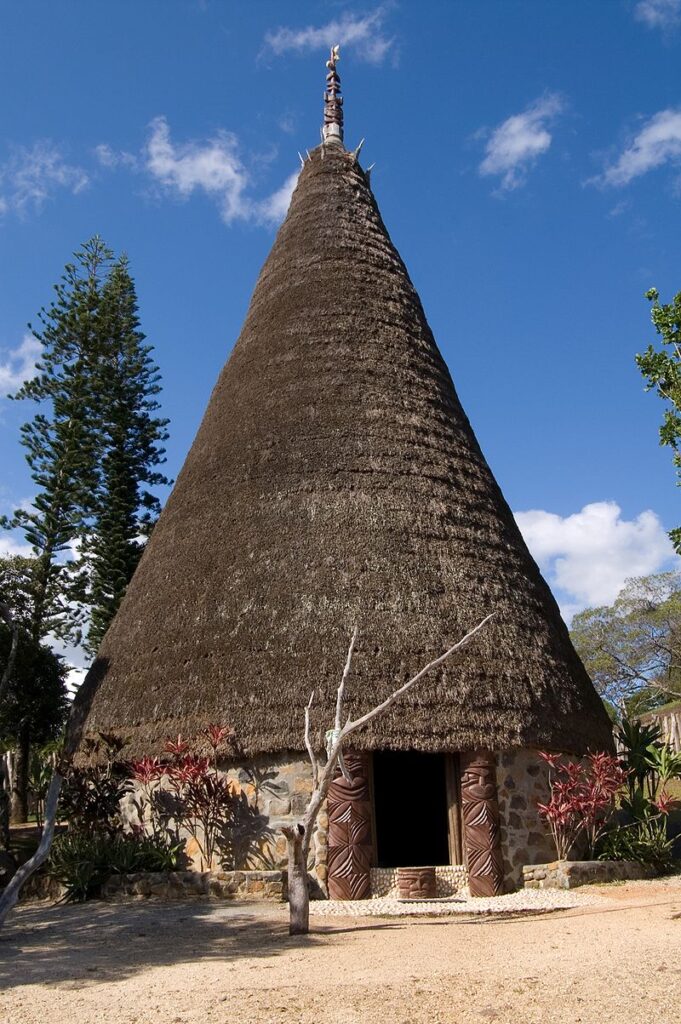

Around the Pacific there are some extremely elaborate examples which have required sophisticated engineering to construct and in turn have withstood some pretty wild weather without any real damage. The Havannah resort on Havannah Harbour in Vanuatu has one of the finest natangura roofs in the country. A soaring conical structure with a modern chandelier beneath is the perfect setting for their fine dining restaurant, along with a much simpler structure on the end of their jetty which can be set up for intimate dinners over the water.

But when it comes to holiday destinations, the thatched roof is everywhere there’s water and sand, from Costa Rica to Koh Samui, Mauritius to Maui (where thatched buildings are called hales), Fiji to Noumea to Africa to Japan to Bali to … well, everywhere.

Another feature of the tropical thatched roof is the beauty of the underside, where the spars are exposed and the elaborate ties form patterns around the battens that secure the palm fronds and the beams. The skills needed to construct these roofs are handed down over generations and the good thing about the renewed interest in using this material is that there is an increasing demand for authentic artisans and the maintenance of the skill base.

Surprisingly there are new buildings in Europe and the UK which still employ thatching as an architectural feature or as a link to the historic foundations of a renovated building. The irony now is that this simple and cheap solution to keeping the elements at bay has become far more expensive and labourintensive than using slate, or metal or tiles or wooden shingles. But the essential beauty of a thatch-clad building is as attractive today as it was centuries ago, and nothing beats it for lazing in the shade by the water.

© 2024 Pacific Island Living Magazine all Rights Reserved

Website by Power Marketing