Solomon Islands

War on Tour

World War II relics and remains have become a tourism sub-industry in Solomon Islands. By Michael Wayne.

August 15, 2023

Pacific Island Living

August 15, 2023On an island they didn’t name, in a conflict they didn’t start, the people of Solomon Islands distinguished themselves with great courage and strength to stop an enemy that regarded them as subhuman.

Their prize at the conclusion of the Second World War was liberation from Japanese occupation and the beginning of the journey to independence.

But decades later, the Solomons still live in war’s long shadow. Battlefields, monuments and relics remain all over the islands, from Malaita in the east to Gizo in the west, and have become a tourism sub-industry.

The majority of the fighting took place on Guadalcanal, the largest of the Solomon Islands, and it’s here that I arrive on a sunny Friday afternoon. Honiara International Airport is the first point of interest for war tourists, built as it was by the Imperial Japanese Army as a landing strip for bombing raids on nearby Allied targets.

During the Battle of Guadalcanal, a brutal six-month campaign, US forces seized the unfinished tarmac and later completed it, naming it Henderson Field after a US soldier killed at the Battle of Midway in 1942.

Another of Honiara’s most prominent long-term Japanese residents is the Kinugawa Maru. The transport ship was fragged in a US airstrike in 1942 and ran ashore at Boneghi Beach, where it sits today.

Kinugawa Maru’s rusty protrusions are a vicious addition to a day at the beach, but for divers it’s a gift. The adventurous can explore the ship’s rear holds, engine and propellers, and encounter its modern crew: an impressive assortment of coral and tropical fish. The wreck’s proximity to the shore makes it ideal for novices.

For a (slightly) more curated experience, however, it’s worth continuing west along Mendana Avenue (Honiara’s main drag) until you reach the Vilu War Museum.

Landowner Fred Kona transformed his plot in the 1970s by hauling wrecks and relics from all over Guadalcanal using his bulldozer and an Opel Blitz truck. Today, Fred’s family runs the open-air museum, which houses an impressive array of decaying aircraft and artillery.

It’s a very at-your-own-pace, self-guided experience. Being face-to-face with these planes and guns in the middle of the Solomon jungle brings the history to life in a way a traditional museum couldn’t. Many are still stamped with 1940s manufacture dates from their factories back in Japan or the US.

The gulf of time between then and now makes it easy to forget that for many, the sacrifices and lessons of war are still vivid. In the hills that collar Honiara’s south are two very different war memorials, one American and one Japanese.

The American one is, as you’d expect, bigger. A blow-byblow account of the US campaign is emblazoned across a series of bold red marble pillars, while the remains of an unknown marine are entombed underfoot. The site is flanked by American and Solomon flags and an amazing view of Ironbottom Sound. The heavy emphasis on remembrance makes this a must-visit for tourists even remotely connected to the war.

The Japanese memorial exists thanks to an entirely other set of motivations. Known as the Solomon Peace Memorial Park, there are fewer words, less colour; white pillars in black gravel. There are the Japanese and Solomon flags and the same stunning view, but there’s much more space for contemplation.

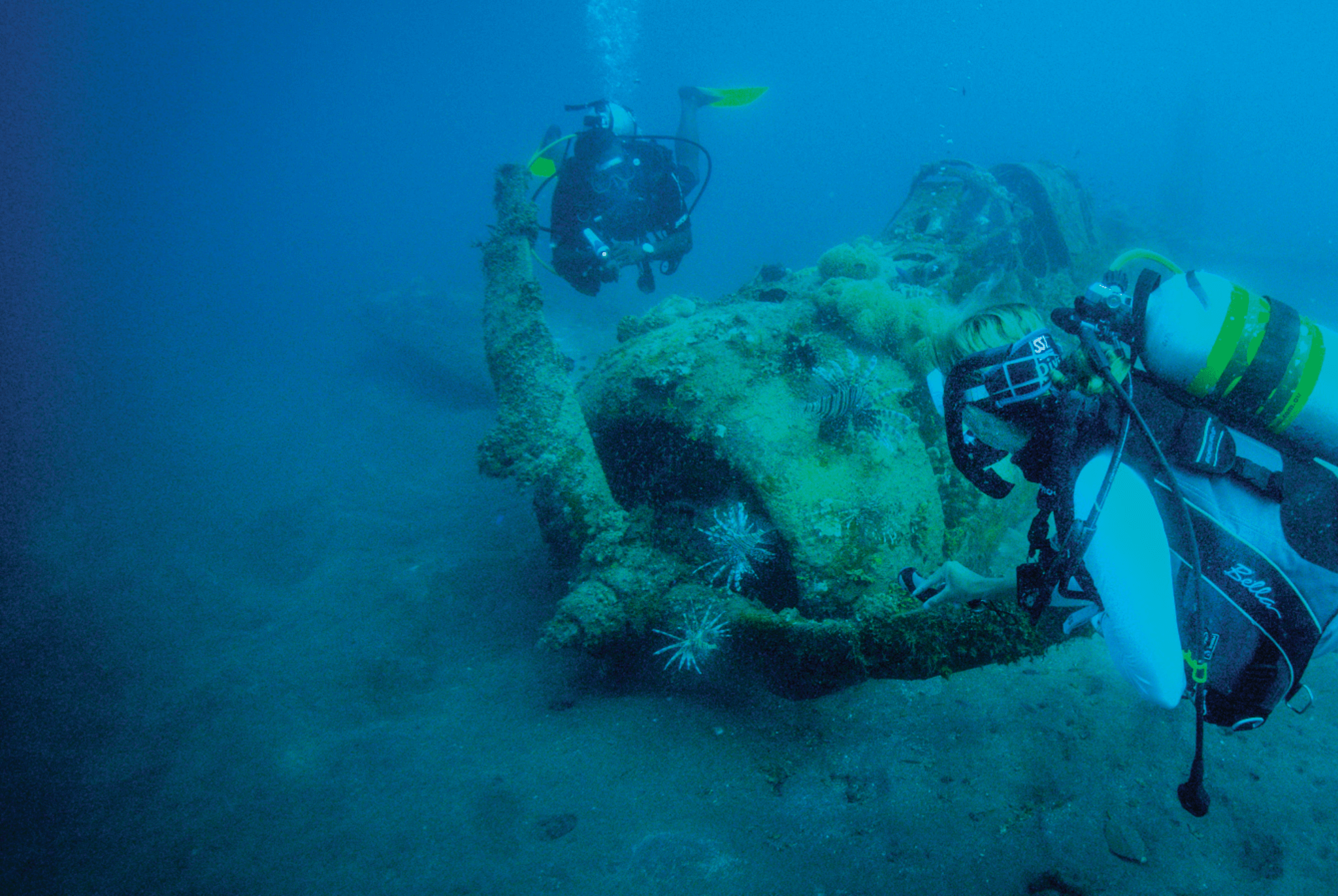

Beyond Guadalcanal, there’s just as much to see. The lagoons of Gizo in the Western Province contain many wrecks that can easily be seen by snorkelers, although full-blown scuba trips are available.

American Danny Kennedy runs scuba operator Dive Gizo, one of the oldest companies of its kind in the Solomons. He’s become an authority on local WWII wrecks in the nearly four decades he’s been here, but says he wasn’t into the war before he arrived.

One of the most popular Gizo dive sites is an F6F-3 Hellcat fighter plane shot down by friendly fire in 1943. Its pilot, Richard Moore, survived and returned to the US, where he died in 1978. Kennedy discovered the Hellcat in 1985, and immediately began researching. “God’s honest truth, I actually scared Moore’s wife with how much I knew about her husband,” he laughs.

Also in the Western Province is Munda, the largest town in the region. Despite this, it’s a sleepy place where locals and tourists bond over beers by the beautiful water.

It was a bit busier in 1943, when US forces spent almost two weeks capturing a Japanese airfield. The fighting was bloody, but the American victory was an important one; the air strip was a crucial part of the Allies’ incursion into occupied Papua New Guinea later that year.

Today, Munda’s backyards are full of war debris. One house I visit has what looks like an enormous tanker standing almost on its end in the backyard; in the front, the driveway is guarded by a huge mounted gun with a helmet dangling on the end.

The most impressive showcase of all is the Peter Joseph WWII Museum, which is run by the affable Barney Paulsen, who possesses an encyclopaedic knowledge of war history and a personal connection to the conflict.

“My uncle was a scout for the Allies,” he says. “The locals were told by the British to work against the Japanese. As a result, no Solomon Islanders helped the Japanese, ever.”

The museum gets its name from a dog tag Paulsen found at Munda Airstrip. “His name was Peter Joseph Palatini. He survived the war, so I tracked him down. At first he wanted nothing to do with it,” he recalls. “But eventually he told me, ‘you can use my name, but not my surname’.”

Peter’s reluctance to revisit the war is typical of veterans who need distance from the horrors they experienced. “These guys close a door after the war was over, and stuff like this opens that door,” Paulsen says. “He didn’t take the dog tags back.”

Those dog tags now join a treasure trove of items in Paulsen’s care, including sidearms, Coke bottles, grenades, heavy artillery, swords and even toys. I check out a wellpreserved deck of Japanese playing cards and dice intended to make downtime more bearable.

Every year, more and more of World War II’s doors close — Palatini passed away in 2019, for instance. But through the hard work and passion of those in the Solomon Islands, whose homes were made battlefields, it’s still possible to at least have a look through the windows.

© 2024 Pacific Island Living Magazine all Rights Reserved

Website by Power Marketing